North Suburban Hammond Organ Service

Pictures of Recent Projects

Metal "Whisker" Formation

Be sure to turn your phone sidewise so that you can see details in these pictures better!

Here is a good look at one of the more unusual problems that can happen to a Hammond organ under certain conditions, and that is the formation of metal whiskers (which are sometimes referred to as dendrites) on many of the steel parts that make up the internals of the instrument. Actually, as I researched the term, it appears that dendrites are metal crystals that resemble tiny ferns or Christmas trees, whereas what I am describing here is called metal whiskering, and these two result from different metallurgical activities. Interestingly, we do not see these whiskers forming on the phosphor bronze contact strips, but they seem to like steel, especially the zinc plated steel that Hammond used for many of the internal stamped parts in the instrument and also on cadmium plated screws.

Fortunately there is an easy and effective way to get rid of these little crystalline metallic hairs, and that is by using compressed air which blows them away very quickly and easily. For doing this, it is best to use a fine needle-type nozzle, and to use air at from 30 to 40 PSI. Generally compressed air for shop use is usually at 90 PSI as that is a standard pressure for pneumatic tools, but you have to remember that some of these Hammond contact parts are quite delicate and generally the lowest pressure that will still get rid of the whiskers is what you should use.

Safety First! Whenever possible, I like to blast metal whiskers and dendrites away outside, because doing it indoors can make lots of little metallic particles float around and you do not want to inhale these. Wear a dust mask, and also wear safety glasses. Actually these are both really smart rules to follow ANY time that you use compressed air for ANY reason at all. It is a good idea to Google the topic of compressed air safety and pay attention to all of the recommendations. And if you have to do whisker (dendrite) removal inside, you should have a second person hold a vacuum cleaner hose close to the area that you are blasting with air so that these tiny metal fibers get sucked away and are not allowed to float around and then settle on furniture and floors. And make sure that second person also wears a dust mask and safety glasses. While we're on the topic of safety, compressed air can make lots of loud and very high frequency noise, so hearing protection is important as well.

Because these metallic crystalline hairs are somewhat conductive, they can cause mini short circuits in any area of a Hammond organ where they form if they grow long enough to bridge to adjacent metal parts. If they form in the percussion switch box, they may stop the percussion from working. Likewise, if they form in or on the vibrato scanner, they can make the vibrato sound very choppy, which is referred to in the trade as "motorboating." In keyboards and pedal switch assemblies, they can make individual or groups of tones much quieter than normal, and may also cause the volume of keys you are already holding down to get quieter if you also play other keys. Although blasting them away with compressed air is very easy, gaining access to the interior sections of a Hammond organ is a very complicated and difficult process. Luckily for Hammond owners, metal whisker and dendrite formation is usually a slow process, often taking years before they appear again. Coating exposed metal parts with a good grade of lacquer is one recommended way to prevent them from reappearing. This is what Hammond routinely did to the edges of the tonewheels to prevent any corrosion from forming which may eventually destroy the precise machined shape and spacing of the lobes on the tone wheels for the highest pitches where these lobes are very small.

I have seen both the term dendrites and also metal whiskering, used to describe this process, and metal whiskering may be more accurate to describe what happens in Hammond organs, where much of the steel plate that Hammond used was zinc plated. Regardless of the cause, the formation of these tiny metallic fibers can create problems, which fortunately are easily corrected but that involves major disassembly of certain sections of the instrument, and thus although the fix is easy, the labor involved can be quite extensive. Certain metals, such as cadmium and zinc are likely candidates to form these whiskers or dendrites. Interestingly, both are applied to steel in order to prevent corrosion. It is worth noting that this particular B3 was for several years in a location not too far from the ocean, and that may have been a contributing factor in what is the worst dendrite or whiskering formation that I have seen so far. Ambient humidity, darkness and electrical fields are all said to increase these occurrences.

If it ain't broke, don't fix it! Regarding dendrites or metal whiskering, following this rule might be something to think about. If a metal whisker doesn't actually contact anything critical nearby, such as grounding a contact or one section of a vibrato scanner, it isn't going to be a problem. Considering how difficult it is to get into Hammond keyboards and pedal switches, vibrato scanners and tone generators, it is probably not a good idea to go after these little metallic hairs if everything is working correctly, And, regarding choppy or "motorboating" vibrato, this is much more often the result of excessive oil on (and in) a vibrato scanner. Some Hammond repair folks recommend zapping the terminals of a scanner with high voltage DC, which you can obtain from the Hammond preamplifier, as a cure for a scanner with such a problem. My opinion is, don't do this! It's somewhat dangerous, has been known to create other collateral problems, and while said to be quick and easy, It does not seem to be a good approach. Besides, if your scanner has so much oil in it that all of the lower stationary plates and their insulating bushings are coated with oil, zapping with high voltage DC most likely won't get rid of the problem. Best approach for an over-oiled scanner is to spend the time and effort to remove it from the console, disassemble it, clean it thoroughly and carefully (denatured alcohol works well for this, because it mixes with the oil, and then when the alcohol evaporates, it takes the oil away with it.) Sometimes you'll need two applications of alcohol, but it works well. After the scanner internals are dry and free of oil, reassemble it, reinstall it and you should be fine, and next time, don't be so generous with that Hammond oil can.

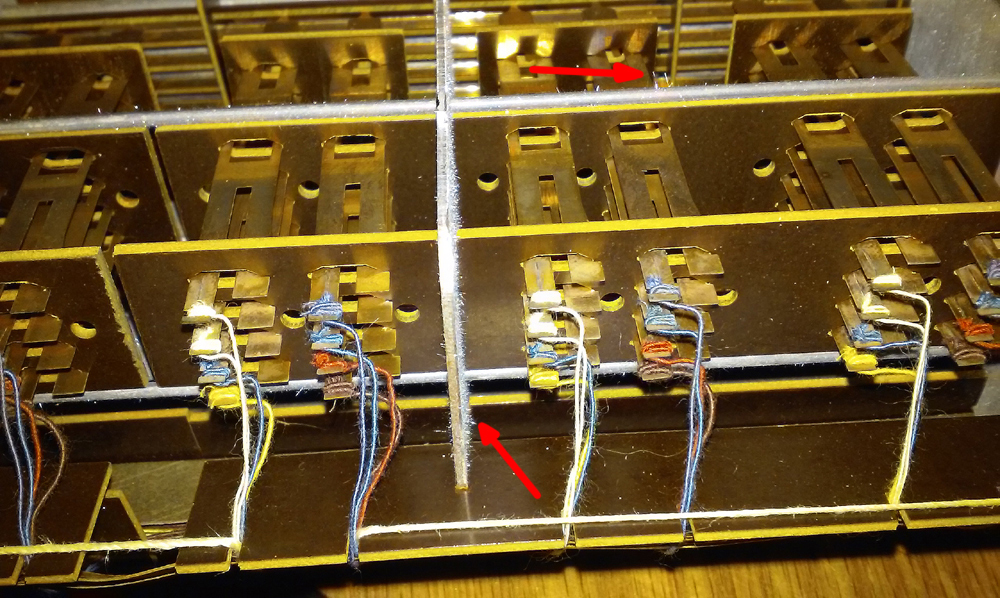

Below I have two pictures of a Hammond organ pedal switch.

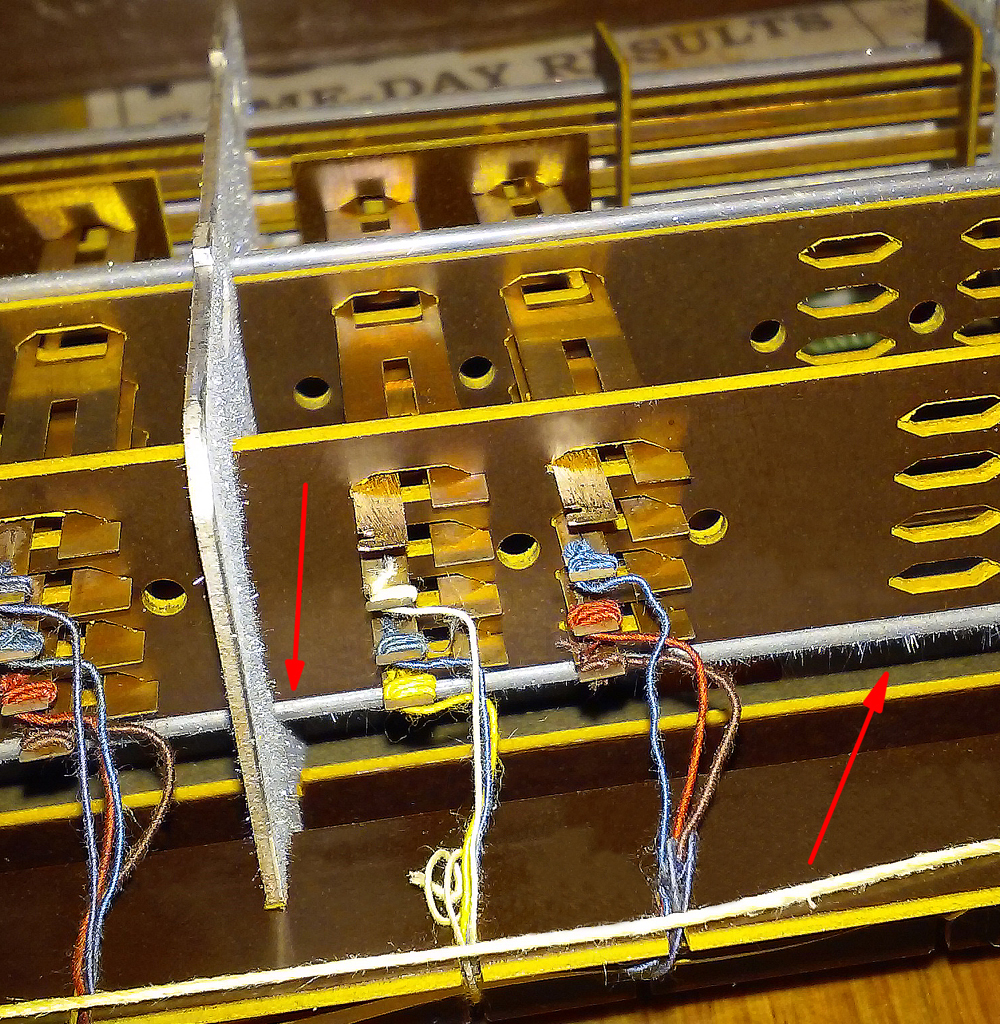

Here is a look at a Hammond B3 pedal switch in which I am preparing to reinstall a TrekII string bass and also MIDI, using the top two original Hammond pedal contacts. These pictures show a serious infestation of metal whiskers, in some places it almost appears that the steel partitions have fur growing on them. Red arrows show dendrites growing on metal parts.

Here's another look. notice that I have removed the original Hammond resistance wires from the top two contacts, and scraped the metal clean in preparation for soldering new 28 gauge magnet wire to these terminals which will then go up into the console for attachment to a TrekII string bass and also to the input of a MIDI multiplexing card. Magnet wire is very good for this work because it has a very thin dielectric coating and makes really neat, small cables which will easily fit through the exisiting Hammond wiring tubes that extend up from the pedal switch on a B style console.