RECORDING the Hammond Organ

North Suburban HAMMOND ORGAN Service

One of the more important things that we often do in modern recording is to record songs in smaller or sub sections called "parts" and then put the parts together into the final production. As I mentioned earlier, suppose that you are recording a Hammond organ and you wish to make a number of changes to the sound, such as changing the drawbar settings for both manuals, changing the vibrato setting, and perhaps even changing the apparant acoustical environment, and make all of these changes right on the beat. Making these changes will take a little time, and that time will definitely interfere with the smooth continuity of the rhythm.

Years ago, this was done by recording the song in parts, that is, record the first part of the song up to the point where you want to make the changes. Then you stop the recording, make your changes, turn on the tape recorder again, and continue playing with the new changes. Although a good tape machine will allow you to make reasonably accurate stops and starts, this will still introduce slight pauses in the recording. Therefore, after making the recording, you will have to edit the tape and actually cut out the resulting short lengths of blank tape and then splice the tape back together accurately enough so that when you play the edited tape, the pauses will be gone and the music will flow smoothly. If you've ever tried to cut and splice tape accurately, you'll know that this is quite tricky and not easy to get right without lots of practice.

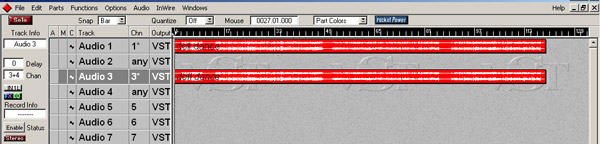

However, when you record digitally, the individual "takes" or "parts" or tracks are stored as digital data files and modern equipment makes it possible to see representations of these tracks either on the viewing panel on a digital recorder, or better yet, on a computer screen. Modern editing software then allows you to "drag and drop" these much as you would any other file, so that you can accurately position them in time. Here's a look at a sound editing screen showing two song parts as we first bring them up on the screen, and then showing how we have moved the second part into position so that as the song plays back, there is a seemless or "bumpless" transfer of the audio from one part to the next with absolutely no extra pauses or interruptions.

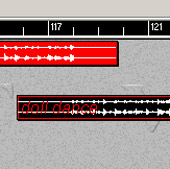

Digital editing is extremely accurate, if you make a mistake it is extremely easy to undo it and try again until the final result is correct. You can see accurately to the millisecond exactly where one part ends and the next part must come in. You can even overlap parts if you want so that one part can "morph" smoothly into the next part. and when you play back the final result, it is absolutely continuous and free of even the remotest trace of any interruption.

Figure 18.Here, in red, are two audio track stereo pairs representating two recording "parts" of the same piece of music on a digital audio editing screen. Notice that both line up exactly, that is, if we were to play this back, they would both play simultaneously.

This we don't want, because the second track pair is supposed to follow, exactly on the beat, the first track pair. So we click on the second track pair and drag it into position, as you see in the next picture, figure 19, below, a closeup which shows the end of the first track pair, and then the start of the second. The audio tracks patterns show up very clearly in this magnified view. Here we can see that right where the audio signals of the first track pair end, they begin for the second track pair. When we make a final mix of these tracks, there will be a smooth, on-the-deat, bumpless transition from the first pair to the second, and absolutely no break in the continuity of the music; just as it should be!

Here we have combined two different track pairs. Both are of the same song, but the second pair is a different part. Notice how the visible audio signals on each track pair line up exactly. When you play this back, there is an absolutely smooth transition from one pair to the next with no break in the continuity or the rhythm of the music.

We at the NSHOS hope you have found this preceding article useful. The subject of successful audio recording is indeed a very complex and involved topic, and this brief essay only touches upon a few significant aspects of the process. As stated earlier, we make no assumptions as to what equipment you have access to, nor for that matter do we even presume to guess how exacting you wish to be. For casual listening, you can certainly obtain passable results by using the built-in microphones of a typical camcorder. Today, even a modern smartphone will do the job passably well. What we have looked at here are the methods that we could use if we wish to get the best possible results, where the impression you get from listening to the recording is that of attending the actual performance and sitting in the "best seats in the house."

When it comes to recording musical programs, this entire article represents only half of the process; namely that of making the recording. The other half of the process concerns what you use to play back these recordings. We can do everything possible at the recording end, but if you play the resulting recording back through a cheap, bargain basement player with inferior speakers driven by a cheap audio amplifier that is full of design compromises to cut costs, the results that you hear will not be all that good. Conversely, if you make a recording using just the mics in a typical camcorder and play it back through a world-class system, you may very well achieve a surprisingly good result. The entire purpose of this article is to present ways in which you can be assured of getting a good recording that should sound acceptable on any system at all, and when you play it through a really first-class system, it should be spectacular; sounding at least as good as being right at the performance itself, and sometimes perhaps even better.

Back to Page 11. Page 12.

Home page